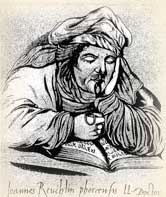

To Johann Reuchlin, Luther owed the Hebrew grammar for his Bible

translation. A man of lowly birth, Reuchlin's talent for singing brought

him to the attention of the Margrave of Baden who made him a companion

of his son. In love with learning, the singer seized every opportunity

his new position afforded to educate himself. Languages were his forte.

He wrote the first Latin dictionary to be published in Germany and a

Greek grammar. Hebrew was his dearest love. He ferreted out the rules of

Israel's ancient language by study of Hebrew texts and converse with

every rabbi who appeared within his range. His authority became widely

recognized.

To Johann Reuchlin, Luther owed the Hebrew grammar for his Bible

translation. A man of lowly birth, Reuchlin's talent for singing brought

him to the attention of the Margrave of Baden who made him a companion

of his son. In love with learning, the singer seized every opportunity

his new position afforded to educate himself. Languages were his forte.

He wrote the first Latin dictionary to be published in Germany and a

Greek grammar. Hebrew was his dearest love. He ferreted out the rules of

Israel's ancient language by study of Hebrew texts and converse with

every rabbi who appeared within his range. His authority became widely

recognized.Reputation was nearly the cause of his ruin. A converted Jew and a Dominican inquisitor extracted from Emperor Maximilian an order to burn all Hebrew works except the Old Testament, charging they were full of errors and blasphemies. Before the edict could be carried out, the Emperor had second thoughts and consulted the greatest Hebrew scholar of the age: Reuchlin.

Reuchlin urged preservation of the Jewish books as aids to study, and as examples of errors against which champions of faith might joust. To destroy the books would give ammunition to the church's enemies, he said. The emperor revoked his order.

The Dominicans were furious. Selecting passages from Reuchlin's writings, they tried to prove him a heretic. Possibly he was. He seemed to expect salvation through cabalistic practices rather than relying totally on Christ's atoning blood. The inquisition summoned him and ordered his writings burnt. Sympathetic scholars appealed to Leo X. The Pope referred the matter to the Bishop of Spires, whose tribunal heard the issue. On this day, April 24, 1514, the tribunal declared Reuchlin not guilty. It was a great victory for freedom of learning.

The Dominicans were not so easily brushed off. They instigated the faculties at Cologne, Erfurt, Louvain, Mainz and Paris to condemn Reuchlin's writings. Thus armed, they approached Leo X. Leo dithered. Should he win applause from scholars by protecting the Jewish books, or placate the clerics? He appointed a commission. It backed Reuchlin. Still Leo hesitated. At last he decided to suspend judgment. This in itself was a victory for Reuchlin. The cause of the embattled scholar became the cause of the innovators. Reuchlin's nephew, Melanchthon, rejoiced. Erasmus praised him.

In 1517 Luther posted his 95 theses. "Thanks be to God," said the weary Reuchlin. "At last they have found a man who will give them so much to do that they will be compelled to let my old age end in peace." Thanks to Reuchlin, the Talmud and Kabbala were preserved. Although he died a broken man, freedom for academic production was strengthened because of his ordeal. Soon his studies formed the basis for better translations of the Old Testament. Furthermore, his influence assured Melanchthon a position among the learned and a place in the Reformation.

Bibliography:

- Hirsch, Samuel A. Book of Essays. Macmillan, 1905.

- Loeffler, Klemens. "Johannes Reuchlin." The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton, 1914.

- Manschreck, Clyde Leonard. Melanchthon, the Quiet Reformer. New York, Abingdon Press, 1958), especially 24, 25.

- Mee, Charles L., jr. White Robe, Black Robe. New York: Putnam, 1972; p. 154ff.

- "Reuchlin, Johannes." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

- Rummel, Erika. The Case against Johann Reuchlin: religious and social controversy in sixteenth-century Germany. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.