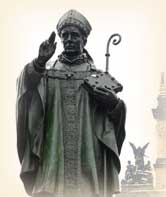

The first known missionary to the Prussians was Bishop Adalbert of

Prague. His work in Prussia followed years of fruitless labor in his

native Bohemia. Paradoxically, it was only by leaving his own people

that he won them.

The first known missionary to the Prussians was Bishop Adalbert of

Prague. His work in Prussia followed years of fruitless labor in his

native Bohemia. Paradoxically, it was only by leaving his own people

that he won them.Born a Vojtech, Adalbert was related to the princely Slavniks. He took Adalbert as his name at confirmation in honor of an archbishop who had supervised his education. Prague's first bishop had been German. On the death of the German, the talented and devout Adalbert replaced him. With great energy and austerity, he set out to reform the clergy and eliminate pagan practices. He sought to extend the range of Christianity among his people. Many pagans clung to their old ways which were nationalistic. Among these was Duke Boleslav of Bohemia. These opposed Adalbert's reforms.

In the end Adalbert's opponents drove him into exile. He entered a Benedictine Abbey in Rome. Four years later, he heeded an invitation to return to Prague. He soon wished he hadn't. Resistance again mounted, and he gave up the fight as a lost cause. A sneak attack by Duke Boleslav wiped out the Slavnik family.

If he could not preach at home, Adalbert would go to other fields. He determined to advance the gospel one way or another. Under the protection of Emperor Otto III, he traveled into Germany, intending to extend his work among the Poles and Magyars. Poland's King Boleslav I invited him to bring the gospel to the Prussians of the Northern coast. Adalbert responded favorably.

In such esteem did the good king hold Adalbert, he made him archbishop of Gnesen. Adalbert proceeded to preach the gospel throughout Poland and to the Prussian shores. This labor of love cost him his life. A pagan priest, jealous, no doubt, for his own prerogatives, murdered him on this day April 23, 997.

King Boleslav I determined to have the martyr's body back. The pagans agreed--on one condition. Boleslav must pay them Adalbert's weight in gold. The King did not hesitate and the missionary's body was brought to him.

Bohemia, which had rejected the martyr while he lived, now clamored for his relics which were reputed to possess miraculous powers. Poland agreed, but stipulated that Bohemia must accept the reforms Adalbert had tried so fruitlessly to introduce while he was bishop among them. The Bohemians accepted these terms and the Roman Catholic ordinances were established.

Adalbert's influence was not yet spent. Moved by the account of the old bishop's death, a young man determined to carry on his work. Ten years later the Prussians murdered St. Bruno of Querfort also. Men like Adalbert and Bruno gave the Medieval Roman church its truest greatness.

Bibliography:

- "Adalbert of Prague." New Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Thomson, Gale, 2002.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine. Lives of the Saints, Vol 4. Edinburgh: J. Grant, 1914.

- Peake, Elizabeth. History of the German Emperors and Their Contemporaries. Lippincott, 1874.

- Various encyclopedia and internet articles.