John Oldcastle was a frank man. As a youth he indulged in pleasures, but coming under the influence of the reform teachings of Wycliffe, he sobered up, purified his ways and started on a new course. Henry V, like Henry IV before him, persecuted the Lollards. His churchmen told him Wycliffe's doctrines were pestilential heresy. Lollards died under Henry's authority. Despite this, Sir John Oldcastle openly avowed Lollard principles.

Perhaps at first he presumed on his former friendship with the king. It is said Oldcastle was the original of Shakespeare's Falstaff, the boon companion of Henry V. Although Henry was for reform, it was not of the type Oldcastle envisioned. Despite opposition, Oldcastle threw open his home to Lollard preachers, making it a base for their operations. He had copies of Wycliffe's works translated and distributed to the continent. In 1413 Henry reasoned with Oldcastle, but the knight stubbornly refused to embrace "mother church" as matters stood, for to do so was to yield to the Pope whom he thought to be the antichrist.

Oldcastle was then commanded to appear before archbishop Arundel, but he ignored the summons. Excommunicated, he responded with a doctrinal statement--a scriptural amplification of the creed. In Medieval fashion, he offered to prove his cause with a hundred knights or in single combat. Finally the old soldier was arrested. On this date, September 23, 1413 he was brought before Arundel where he presented his confession of faith. Salvation is in Christ alone without intermediaries. This was acknowledged to be, in the most part, sound Catholic doctrine.

Some days later Oldcastle clarified his position on two doctrines where the established church and he were in disagreement: the Eucharist and confession to priests. He insisted the bread was still bread (did not become the literal body of Christ) and said that while it might be helpful to confess to a priest, it was not essential for salvation. A heated argument developed with both sides hurling texts of scripture until Oldcastle grew angry enough to denounce the pope as antichrist. This was no new position with him, but it sealed his fate; years earlier he had spoken openly against the papacy in Parliament. Now, however, Oldcastle warned the bystanders they were in danger of hell if they continued in the teaching of his Catholic judges.

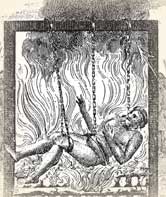

Arundel condemned him to death as a heretic. Because of Oldcastle's friendship with the king and high social standing, he was given forty days to recant. During that time, he escaped and hid in Wales. An immense reward was offered for him dead or alive. Nonetheless he remained hidden for four years. At last someone betrayed his whereabouts. Oldcastle was captured, hanged briefly and then suspended in iron chains over a fire and roasted to death. The English Reformation would have to wait until a future century, but ardent believers such as Oldcastle helped prepare England for it.

Bibliography:

- Armitage, Thomas. A History of the Baptists; traced by their principles and practices, from the time of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ to the present. New York: Bryan, Taylor and co., 1893. Source of the image.

- Durant, Will. The Reformation; A history of European civilization from Wyclif to Calvin: 1300 - 1564. The Story of Civilization, Part VI. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957; pp. 116 - 117.

- "Oldcastle, John." Dictionary of National Biography. Edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. London: Oxford University Press, 1921 - 1996.

- "Oldcastle, Sir John." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

- Wylie, J. A. History of Protestantism. 1878.