Warning signs? ‘Silent Earthquakes’ ripple under Cascadia

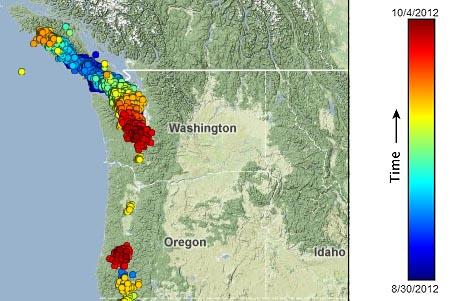

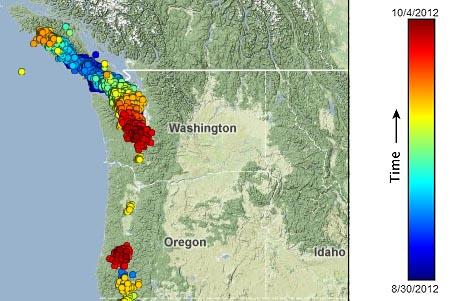

October 6, 2012 –WASHINGTON - Parts of Washington and Oregon are in the midst of silent earthquakes this week. You can’t feel this so-called “slow slip” quake and it doesn’t cause damage. Still, scientists want to learn more about the recently discovered phenomenon. Little is certain so far, but there’s a possibility these deep tremors could trigger a damaging earthquake or serve as a warning bell for the Big One. A bank of computer monitors covers one wall of the University of Washington seismology lab. Some display seismograph readouts that look like jagged mountain ranges stacked one over the other. A big screen shows a current map of tremors under the Pacific Northwest. It is lit up with activity. “Each dot represents the location of a five minute burst of tremor,” says earth scientist Ken Creager. He scrutinizes a dense slash of blue, yellow, green and red dots. The arc stretches south from mid-Vancouver Island, goes under the Olympic Peninsula, Puget Sound and peters out south of Olympia.

A separate patch of color radiates out from near Roseburg, Ore. Washington State Seismologist John Vidale is also keeping an eye on the busy map. “This kind of earthquake is distinctly different than the earthquakes we have been watching for a hundred years, because this patch of fault that we’re watching takes three weeks to break. Whereas ordinarily something a hundred miles long would take a minute or less to break. About half of our instruments can see it,” Vidale adds. “It’s a very slight level of rattling. I don’t think I have ever heard of somebody who we believed could feel it.” Local seismologists woke up to the phenomenon about a decade ago and have since discovered a big non-volcanic tremor swarm happens fairly routinely around here — every 14 months or so in western Washington, a little less often in Oregon and more often in northern California. Scientists have coined a variety of names including “slow slip quake” or “episodic tremor and slip” to describe what they’re seeing. Vidale says the mechanisms at work deep underground remain fairly mysterious. This current slow slip quake under the Salish Sea has lasted five weeks. Creager says scientists have calculated that a significant event like this releases the equivalent energy of a magnitude 6.5 regular quake. “It’s a lot of energy being released,” Creager says. “It just happens so slowly that you’re not going to feel it. This is the way we like to see energy released.” But there’s a flip side. The grinding and slippage at depth increases the strain closer to the surface where the North American plate and the oceanic plate are stuck together or “locked.” When that offshore fault zone eventually gives way, we get the damaging Big One. University of Oregon Professor David Schmidt makes an analogy to a car teetering partway over a cliff. “And these small slow slip events are somebody standing behind that car giving it a little nudge every several months. So even though the nudge is small, at some point that nudge might be enough to kind of tip us over the edge and cause the car to fall off the cliff.” Or set off the Cascadia mega-quake in this analogy.

Schmidt points to a study published in the journal Science that describes how last year’s great earthquake and tsunami in Japan was preceded by slow slip and tremor near the epicenter. John Vidale mentions another killer earthquake, in Turkey in 1999, where instruments picked up a slow slip precursor. “One of the goals of our research is to say, how often does that slow slip trigger a great earthquake? How often are great earthquakes triggered by slow slip? That’s almost completely unknown at this point.” Vidale and his colleague Creager are more certain that we don’t need to quake with worry. They note that great earthquakes strike very infrequently in the Northwest. So even if a megaquake becomes more likely during a slow slip event, the chances of one happening are still quite slim. –Northwest Public Radio