The people who are making cyborgs a thing of the present

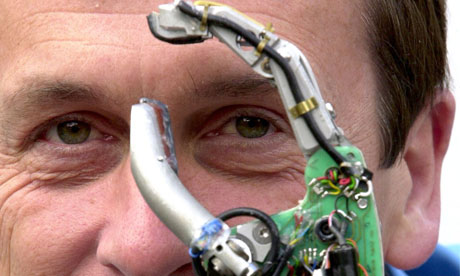

Professor Kevin Warwick and his cybernetic arm. Photograph: Rex Features

Many of us are already cyborgs. If you have a contraceptive coil fitted, or a pacemaker – arguably even if you wear contact lenses or have pierced ears – then you are in a sense part-human and part-machine. For a small but growing global community of "biohackers" or "grinders", however, there is far more fun waiting to be had.

A common procedure is to implant a strong neodymium magnet beneath the surface of a person's skin, often in the tip of the ring finger. This causes nearby magnetic fields – and even their strength and shape – to become detectable to the user, thanks to the subtle currents they provoke. For a party trick, they can also pick up metal objects or make other magnets move around.

Calling this a procedure, though, gives rather the wrong impression. Biohacking is not a field of medicine. Instead it is carried out either at home or in piercing shops, cleanly and carefully with a scalpel, but without an anaesthetic (which you need a licence for). If you think this sounds painful, you are correct.

Britain is the birthplace of modern transhumanism, as the field is known. Probably the most sophisticated implantation ever made can be found inside the left arm of Kevin Warwick, professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading, who can now control a robot arm by moving his own. The system also works the other way, so he can now sense his wife's movements in his own body, after she had a similar implantation.

A more intuitive exponent is Lepht Anonym, the name used by a young woman in Aberdeen, who has performed many adaptations on herself at home using nothing more sophisticated than sharp implements and vodka. She began with a sensor that allowed her to lock and unlock her computer, and then fitted a temperature display that emerged through the skin, though this was not a success.

To Warwick, Anonym and the wider grinding community, who meet online in forums such as biohack.me, implanted technology or "wetware" represents the next stage in mankind's evolution. And, indeed, the idea is not outlandish. Brain stimulation from implanted electrodes is already a routine treatment for Parkinson's and other diseases, and there are prototypes that promise to let paralysed people control computers, wheelchairs and robotic limbs.

Last week, X-Men producer Bryan Singer launched a web TV series called H+ prophesying the cataclysmic consequences of all this. Yet the ultimate potential, for good or bad, may be even greater than it imagines. "Bringing about brain-to-brain communication," Warwick says, "is something I hope to achieve in my lifetime."

A common procedure is to implant a strong neodymium magnet beneath the surface of a person's skin, often in the tip of the ring finger. This causes nearby magnetic fields – and even their strength and shape – to become detectable to the user, thanks to the subtle currents they provoke. For a party trick, they can also pick up metal objects or make other magnets move around.

Calling this a procedure, though, gives rather the wrong impression. Biohacking is not a field of medicine. Instead it is carried out either at home or in piercing shops, cleanly and carefully with a scalpel, but without an anaesthetic (which you need a licence for). If you think this sounds painful, you are correct.

Britain is the birthplace of modern transhumanism, as the field is known. Probably the most sophisticated implantation ever made can be found inside the left arm of Kevin Warwick, professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading, who can now control a robot arm by moving his own. The system also works the other way, so he can now sense his wife's movements in his own body, after she had a similar implantation.

A more intuitive exponent is Lepht Anonym, the name used by a young woman in Aberdeen, who has performed many adaptations on herself at home using nothing more sophisticated than sharp implements and vodka. She began with a sensor that allowed her to lock and unlock her computer, and then fitted a temperature display that emerged through the skin, though this was not a success.

To Warwick, Anonym and the wider grinding community, who meet online in forums such as biohack.me, implanted technology or "wetware" represents the next stage in mankind's evolution. And, indeed, the idea is not outlandish. Brain stimulation from implanted electrodes is already a routine treatment for Parkinson's and other diseases, and there are prototypes that promise to let paralysed people control computers, wheelchairs and robotic limbs.

Last week, X-Men producer Bryan Singer launched a web TV series called H+ prophesying the cataclysmic consequences of all this. Yet the ultimate potential, for good or bad, may be even greater than it imagines. "Bringing about brain-to-brain communication," Warwick says, "is something I hope to achieve in my lifetime."